Five years ago today, Iron Pioneers was published. I started writing The Marquette Trilogy in 1999 and nearly seven years later, I finally had the first volume published. It was a scary and exciting moment for me as I wondered whether what I had spent so much time writing until I loved the book like it was my own child would be received by the public. Obviously it was since I now have eight books to my name.

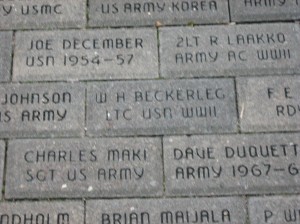

![iron_pioneers_cover[1]](https://tylerrtichelaar.files.wordpress.com/2011/02/iron_pioneers_cover1.jpg?w=198&h=300) To celebrate Iron Pioneers five year anniversary, I am posting not the Prologue or the first scene but the second scene of the novel, following when Clara and Gerald have arrived in 1849 to the little wilderness settlement called Worcester and whose name was soon after changed to Marquette. In this passage, Clara meets the Harlow family and Peter White, who are among the most famous names in Marquette history. To get a copy of the full novel, visit http://www.marquettefiction.com/iron_pioneers.html

To celebrate Iron Pioneers five year anniversary, I am posting not the Prologue or the first scene but the second scene of the novel, following when Clara and Gerald have arrived in 1849 to the little wilderness settlement called Worcester and whose name was soon after changed to Marquette. In this passage, Clara meets the Harlow family and Peter White, who are among the most famous names in Marquette history. To get a copy of the full novel, visit http://www.marquettefiction.com/iron_pioneers.html

Enjoy!

From Iron Pioneers:

When Clara woke, it took her a few seconds to remember she was no longer on a boat, or a train, or in her comfortable bed back in Boston. Above her was a wooden roof with a crack that revealed the sky. She crawled out of bed and onto boards laid across a dirt floor. Since Gerald was already gone, she feared she had slept later than she should; from the crack in the ceiling, she could tell it was already daylight. Last night, she had been relieved to have a roof over her head and a bed to sleep in, but now this dingy little partition of a room made her hope Gerald would not be long in building her a decent house.

Last night, she had hardly more than glanced at the other buildings in the village. She had noted the rough exterior of the Harlows’ house and that of Mr. Harlow’s assistant. Both buildings had been rundown fishing huts moved from farther down the lakeshore to serve as temporary residences. Clara was surprised to find herself envious that Mrs. Harlow had her own house, no matter how dilapidated its condition. Even if at this moment, Gerald were purchasing them a plot of land to build on, she knew she could not expect more than a small one-room cabin this first year. Winters here were supposed to be long and harsh and to arrive early, so Gerald would have to build soon and spare no time for fancy details if they were to have a shelter before the first snowfall. It was August, but as Clara emerged from her makeshift bedroom, she could already imagine the fierce winter winds.

She found Mrs. Wheelock in the kitchen cooking breakfast.

“Your husband went to look around the village, but he told me to let you sleep,” said Mrs. Wheelock. “I know how tiring the long journey here can be.”

Clara thanked her hostess as Mrs. Wheelock placed eggs and bread before her. She wished Gerald were here, but she understood he had work to do. Mrs. Wheelock said he had promised to return by noon, and he had suggested she call on Mrs. Harlow that morning.

“I’ll visit her as soon as I finish eating,” Clara replied. Mrs. Wheelock planned to go wash up the dishes, but Clara asked her landlady to stay and talk while she ate, in return that she help her with the dishes. Clara had never washed a dish in her life, but she was not so spoiled that she did not understand she would have no servants here as she had in Boston.

Mrs. Wheelock gladly sat down to rest a few minutes. She told Clara how quickly her boarding house had filled with guests, and that she had her hands full cooking and doing laundry for the inmates. She was thankful to have a female guest if only to have someone to talk with. Clara had nearly finished her breakfast when a young man stepped into the house. He was about her age; Clara assumed he was Mrs. Wheelock’s son until he introduced himself.

“Hello, I’m Peter White,” he said. “I’m a boarder here. You must be Mrs. Henning.”

“Yes, I’m pleased to meet you,” she replied, taking his offered hand.

“Peter is one of the youngest and most active members of our settlement,” said Mrs. Wheelock. “In fact, he helped to build the first dock. Peter, why don’t you tell Mrs. Henning about it?”

Peter laughed as Clara prepared herself for a humorous tale.

“Well, any city needs a good dock,” began Peter, “and we were determined ours would be one of the best. Captain Moody was in charge, and in no time at all, he had us hauling entire trees into the water and piling them crossways until we had built two tiers from the lake bottom up level with the water. Then we covered it all with sand and rocks. In just two days, we had the dock finished. We believed we had accomplished the first step in transforming Worcester into a future industrial metropolis. We imagined a hundred years from now our descendants would look upon the dock and praise us for our ingenuity.”

Clara smiled at Peter’s self-mocking tone.

“Next morning, imagine our surprise when we discovered one of Lake Superior’s calmest days had been enough to wash the dock away. Not a single rock or log was left behind to mark where it had been. The sand was so smooth you never would have known the dock existed. How easily man’s grandest schemes succumb to Nature’s power.”

There was a moment’s pause while Peter smirked. Then Mrs. Wheelock scolded, “Peter, be fair. Finish the story.”

Peter grinned but obeyed.

“The entire episode was so comically tragic I could not help but feel some record of it should remain for the city’s future annals. I took a stick and wrote on the sand, ‘This is the spot where Capt. Moody built his dock.’ Well, Captain Moody took one look at that and wiped it away with his feet. He was apparently not as amused as I was, and he told me I would be discharged from his service at the end of the month.”

Clara had been smiling, but the story’s conclusion saddened her.

“What a shame. You didn’t mean any harm by it, and it was as much your work as his that failed.”

“I was sorry to offend him,” Peter confessed, “but he hasn’t dismissed me yet. Either he quickly got over his temper or he’s forgotten about it. I’m certainly not going to remind him.”

“I’m sure Captain Moody has forgiven you by now,” said Mrs. Wheelock. “He realizes what a blessing you’ve been lately. Mrs. Henning, I don’t wish to scare you, but there’s been an outbreak of typhoid fever here. Nearly everyone has now recovered, so there shouldn’t be anything to worry about, but we can all thank Peter for his hard work. He has bravely cared for the sick, even bathing them at risk to himself.”

Peter ignored the praise to explain further. “We recently had a large number of foreigners arrive in the settlement. Mr. Graveraet brought them up by boat from Milwaukee to work. Most of them are German, but there are a few Irish and French among them. Almost all of them got typhoid on the trip here and several died before they arrived. It’s a sad situation, so I did what I could for them. Everyone has been taking turns helping.”

“It isn’t as bad as we first feared,” Mrs. Wheelock told Clara. “We thought it might be cholera; that was enough to scare the local Indians into deserting the area, but then Dr. Rogers determined it was only typhoid, though that’s bad enough.”

“There’s only a handful still recovering,” Peter added. “And no one else has contracted it, so it can’t be contagious anymore. I’m sure it’s nothing to be concerned over, but we could use a little more help caring for the sick.”

“Oh,” said Clara, terrified at the thought, yet anxious to do her share of work in the new community; she knew she would need friends to lend her a hand in future hardships. “I’d be happy to help with the nursing.”

“We wouldn’t want you to become ill too,” warned Mrs. Wheelock.

“Oh, but I can’t let those people suffer if I can help them,” Clara said to mask her fears.

“I could show you the building we’re using for a hospital,” Peter offered. “Then you can decide if you want to help.”

“All right, I should be free this afternoon,” Clara replied, “but I promised to call on Mrs. Harlow this morning.”

Peter agreed to come fetch her after dinner and thanked her in advance for her help; Clara felt a sudden fondness for this young man who seemed so bright and capable. She did not believe even typhoid could lessen his liveliness.

After Peter rushed off, Clara helped Mrs. Wheelock wash up the breakfast dishes. She also inquired more into Peter’s history.

“Oh, Peter is quite an adventurer,” replied the landlady. “He’s been all over the Great Lakes working on boats, doing various types of work.”

“How old is he?” asked Clara.

“Only eighteen,” said Mrs. Wheelock, “but he’s already an old timer in terms of knowing this country. His family is from New York, but when he was nine, they moved to Green Bay, Wisconsin. Then when he was fifteen, he basically ran away from home and went to Mackinac Island; ever since, he’s been exploring the Great Lakes and working at whatever he can find. Last spring, Mr. Graveraet hired him to help with the iron company, and he’s been living here since.”

“What an adventurer,” Clara said. Even Gerald’s courage in coming to this region seemed small beside a fifteen year old boy traveling all over these dangerous lands.

Once the breakfast dishes were finished, Mrs. Wheelock went to start the laundry before she needed to prepare lunch. Clara decided to act on her promise to visit the Harlows. Mrs. Wheelock pointed the way to their dilapidated hut; then Clara started down the path through the little settlement. Along the way, she glanced at the tall, unfamiliar trees that surrounded the few scattered buildings. She had never before seen so many trees stretching for so many miles. She wondered what ferocious beasts might lurk in those woods. Even in the forests of Massachusetts, it would only be a mile or two until a person saw a house or farm, but here one could walk for days without seeing another human being. Worse, a bear might be encountered. Frightened by the thought, Clara scurried to the Harlows’ hut, wishing someone were in sight in case of danger.

She found Mrs. Harlow and her mother, Mrs. Bacon, occupied with sorting the new supplies Mr. Harlow had brought from Sault Sainte Marie. After introductions, Clara’s first remark was about how nervous she felt to be outside alone, but Mrs. Bacon assured her she was perfectly safe. “No one will harass you here, and we aren’t established enough to worry about such social proprieties as a woman walking without her husband. You’re as safe here as on the streets of Boston.”

“But are there any Indians nearby?” Clara asked.

“Yes, but the Chippewa are perfectly friendly,” Mrs. Harlow added. “They’ve been very kind to us since we arrived a few weeks ago.”

“Olive, tell her about your first meeting with a Chippewa,” laughed Mrs. Bacon.

“Oh,” Olive laughed. “My first morning here, I was determined to see everything I possibly could about my new home. I stepped out my front door and practically the first thing I saw was a wigwam. I’d never seen one before, and I was just so curious it never suggested itself to my brain that it might be someone’s home. So I went over and opened up the blanket door, and to my amazement saw two squaws. At first I was surprised, and a little frightened, but they smiled and giggled, and then I giggled back and retreated.”

“I would have been terrified!” Clara gasped. “You’re lucky they weren’t male Indians.”

“Oh, the male Indians are just as kind as the women,” replied Mrs. Harlow. “They’ve already assisted us a great deal. Chief Marji Gesick has been very kind by stopping to inquire how we are all coming along, and Charley Kawbawgam has an Indian village not far away on the Carp River. He’s been showing the men the best hunting and fishing grounds, and some white men are even staying in his lodge house. Granted, we’ve only been here about a month, but so far, there’s been no need to worry, and our hearts are strong. Now that my husband has brought us some more supplies, we should have little trouble getting by for several months. I don’t think it’s going to be easy, but I feel this little settlement will grow and prosper faster than one might suspect.”

“Yes,” said Mrs. Bacon, “the men had the dock built in just three days, and the sawmill and forge should be finished before winter arrives. It may not be until next year that we really become a businesslike town, but it will happen soon enough.”

Clara smiled, but she was presently more concerned about the settlement’s safety than its prosperity.

“I can’t believe how this country is changing,” added Mrs. Bacon. “I was born just about the time President Jefferson made the Louisiana Purchase, and since then the country has more than doubled in size. When I was a child, no one ever would have imagined Michigan becoming a state, and here it’s already been one for a dozen years. Just imagine, Mrs. Henning, how much this town will have grown by the time you’re my age.”

“Yes,” said Clara, “but I’m afraid it will be a lot of work along the way.”

“Hard work is what we’re put on this earth for,” replied Mrs. Bacon. “Besides, we have it easier now than any of our forefathers ever did, and after how they struggled to make this nation what it is today, we have to carry on the tradition of that hard work.”

Clara recalled her grandmother uttering similar sentiments. She thought again of her ancestress, Anne Bradstreet, trembling upon arrival in the New World, only to become a famous poetess and one of the first ladies of the land, daughter, wife, and sister to colonial governors. Clara wondered whether someday she might equally be remembered as a pioneer of this rugged place. If the iron ore recently discovered made them all as rich as predicted, and Worcester grew as large as Boston, she might delight her mother by becoming a leader of Worcester society.

But Clara had not come to gain wealth or social position. She reminded herself she had come to support her husband, and to prove she had the courage to surmount challenges rather than settle for the dull social rituals of Boston. For the first time, she felt excited to be living along the shores of Lake Superior. Her travel fatigue was lifting, and she felt anxious to see the rest of her new home, despite what dangers might exist in the forests. So Mrs. Harlow and Mrs. Bacon could return to their work, she soon excused herself.

“I think I’ll go for a walk along the lake before Gerald returns at noon.”

“Go ahead,” said Mrs. Harlow. “You might as well enjoy your first day here.”

“Yes, I told young Mr. White I would go to the hospital this afternoon to help.”

Mrs. Bacon and Mrs. Harlow exchanged approving glances. Clara’s heart glowed inside her–she had been afraid people would think her some frail young miss from high society, but already she felt she was proving herself.

As she stepped out of the wooden hut, she scanned the other log cabins under construction. A few wigwams and a lodge house were in the distance; she wondered whether Indians resided in them or had white men taken possession. Scarcely enough buildings existed to qualify as a village. She looked down to the lake where the lone dock stood. The schooner had already disappeared from sight, leaving no chance to escape. Lake Superior stood before her–the only source of communication with the outside world–so large she could not see Canada across it. How long before another ship would come, before ships would come regularly? It might be years before there was a railroad or even paved streets, before there would even be stores in which to buy trinkets, or cloth, or even food. There wasn’t even a butcher–Gerald would have to hunt for their meat, and they would have to plant their own vegetables. She wondered how much land they would have to plant to feed themselves. Mr. Harlow had told Gerald sixty-three acres had been purchased for the village to expand upon, but only a few acres were now cleared. She could not imagine the settlement ever growing enough to cover that much land. The trees would only encroach back in. All around her were towering pines, oaks, and maples. So many trees–a giant unexplored forest all around, full of mystery, perhaps horror.

“Clara!”

She turned to see Gerald walking toward her with Mr. Harlow. He was beaming.

“I’ve found the perfect place for our house. A few of the other men have agreed to help build it, and when they heard I had a wife, they said we could raise our roof first, and then I can help them later. We should have our own shelter within the week.”

“That’s good,” Clara smiled. “Then I’ll have a place to put my china.”

“More than that,” said Gerald, “we’ll have a home, and I’ll fill it with homemade furniture. Isn’t it exciting, Clara? It’s a whole new world for us.”

She hesitated to reply, but Gerald’s enthusiasm won her over; he was so free from self-doubt, so charismatically able to make others believe in him; she believed in him. His confidence was what made him most attractive to her. If they did not survive here, it would not be through the fault of this brave man she loved.

Clara took his hand.

“It’s a fine land, Gerald. I’m sure we’ll be happy here.”

Mr. Harlow smiled in recognition of the same courage his own wife possessed. Maple leaves rustled in the breeze, as if confirming Clara’s words. Gerald once more felt he had made the right choice in his bride, in this brave, beautiful young woman.

![iron_pioneers_cover[1]](https://tylerrtichelaar.files.wordpress.com/2011/02/iron_pioneers_cover1.jpg?w=198&h=300)